The Business Behind A Passion: Chi Modu Interview (Part II)

Chi Modu has had a fascinating career as a photojournalist. In Part I of our interview we talked about his experiences involving the world’s biggest Hip Hop artists and his latest project, UNCATEGORIZED. In the second half of our chat Chi talks about the business behind his passion, the changing face of photography and social media.

You mentioned social media and the difficulties of ensuring that people recognised your work as yours. With it being so easy for people to share media online now, is it harder as a photographer to make sure that you receive credit and recognition nowadays?

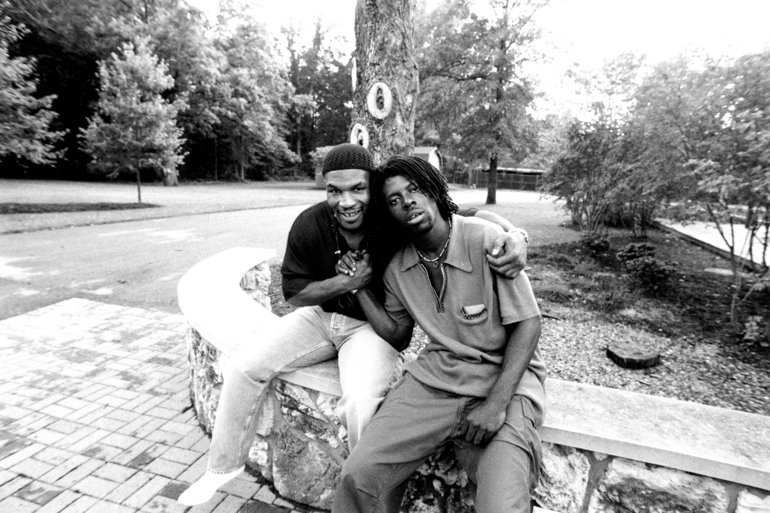

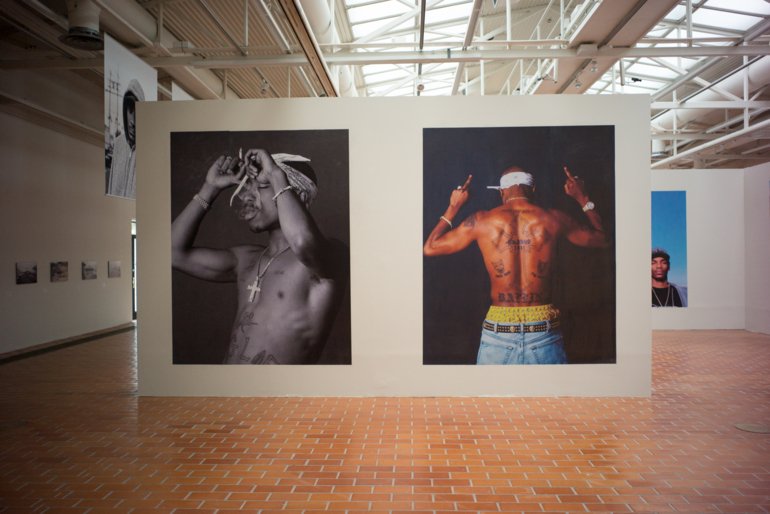

I’m 50 years old, so I come from the film era, the “defend, defend, defend” space, where you had to watermark, block, don’t let them get it. But that’s not the world we live in today. I think for me to say this to you is very advanced and you won’t find a lot of my peers able to say this, because they were defending when the world stopped defending, but what I decided was that I was going to go with a public watermark, because I was going to flood the market and so by default if you see a photograph of a rapper that’s a good one [high quality] you’re going to think I took it. For people that I came up with, they would have never gone this route, because I’m releasing pictures of Tupac I’ve never released in 20 years and I’m giving it to the public to see on [social media] and all I ask is that you credit me. That’s it. Now, most people do gladly – but the few people that don’t, I have other people that will go in and police that, because you end up having like these soldiers that are the public and they want to protect you, so I feel that my work is more protected now than when I was protecting it by myself. So that’s the shift that has occurred.

There’s an advertising campaign that a well-known brand recently ran which claimed the photos used were “inspired by” your work. I know some of your followers on social media felt there were perhaps too many similarities between the images to call it “inspiration” and this maybe presents another issue for the industry – how can photographers protect themselves against that?

You can to a point. There are some legal options in those areas, but you can’t fight everybody all the time. The local guy bootlegging a picture of mine on a t-shirt for themselves and a few friends, I just think “do your thing”, but if you want to then manufacture something en masse and make money from it, cut me in. Those are my only rules. But I’m not one of these guys that thinks like “how dare you repost my photo!”, do your thing. I’m a photographer, not just someone that defends all day long. But I think that’s also partly why the public likes me and is so protective and respectful. You’ll see on my instagram I engage with my follower, but not really that much because you can’t manage that many human beings and it’s more like a one-way conversation, but you let them know that you appreciate them by continuing to show them respect by how and what you post, that’s the way I show them thanks.

What are the biggest changes you’ve had to adapt to as a photographer?

The whole photography industry has changed. Right now, there are less jobs but photography is more important. That sounds a little crazy, but it’s a fact and photography is more important than it ever was. Magazines have shrunk, less are printing, it’s a different kind of approach to the skill that you had. Remember, The New York Times, Time Magazine, that’s where we would go after ICP, but after a while I had to turn my nose up to those things that were turning their nose up to me. What’s funny is those things that were turning their noses up to me are now gone, I remember News Week used to license pictures on a regular basis and now they don’t even print anymore. A lot of these places would license but never hire me to shoot. So I got into a habit of just licensing and not shooting, and in fact it became more profitable and easier for me to license and not shoot. If they’d asked me to I realised the work it takes to shoot and I would have done it, but once they didn’t ask me I then eventually didn’t want it anymore. But what happened to all these places that were the gatekeepers, they’ve shrunk – The New York Times photo department has shrunk, it’s just how it is.

Sometimes we’re fortunate when we’re outsiders because we’re prepared for the shift much better than those who have been eating off the man – when you have to eat off the land and the people we’re prepared when the money goes away because we’ve not had access to it. So my photo life and world has always been entrepreneurial based. I’ve always had to figure out what is the end product of my imagery, and it’s not somebody else’s publication. I’ve done skateboard decks, t-shirts, exhibitions, auctions, for me an image is a product. And it’s up to me to figure out how that product is represented and sold. Traditionally, people have left it to the magazine how they’re going to figure out how to sell their product and they’re sitting waiting for their phone to ring. But I don’t wait for the phone to ring, I don’t eat because my phone rings, I eat because I go make it happen. A lot of people still think someone wanting your image is what makes it a product, but it’s not, it begins as a product and you have to figure out how to use it. I look at my pictures as my products, my assets and I have to figure out how to monetise my assets, not anybody else. So I take a businessman’s perspective and that’s why I embraced the stock business when I did, because I knew I had a certain value that no-one else had, so I had an advantage within the space. I’m not the guy that shoots the foliage in New England, that’s not my thing, there are plenty of people who do that beautifully, but I’m not competing with that guy.

Do you still find time to shoot even though a lot of your focus turned towards licensing and the stock image business?

All the time! I travel around the world a lot, my other Instagram page (@MrLeicaM) is my stuff around the world. At my core I’m a photojournalist and that’s the reason I did Hip Hop, because I was documenting a movement – and it was just as important as the stuff I do in Yemen, Syria, Pompeii, because you’re documenting people. With my projects around the world I figure out a way to pay for it, but I always look at the money for my imagery not coming just from the place that paid me for it, but from other things that I can come up with outside of it. Like I said, the pictures are the products for me, so no matter what I do it’s always done where I have to figure out how I can make it go beyond just that assignment. Whatever someone pays you to do something that’s never enough, because that’s going to be spent and then you’re not going to be able to make any more back. If you look at my music photography I own all the rights to that stuff so it continues to generate for me long after I’ve done it. The medium I did it for, The Source, is no longer even in print, but the content I did still is used almost daily around the world in different platforms. Mediums come and go and change, but the content is what really holds up.

Do you still do any work within the music industry?

It’s funny you ask that, I was just saying to someone the other day that that work for me today just seems so boring, and you can tell I don’t like boring! 20 years ago it was fun because there was an energy, we were charting new ground and there was a passion. Now it’s become somewhat formulaic and that’s not to say all creativity is gone, but it’s more formulaic than I’m used to. I could do whatever I wanted, somebody would show up and say “Chi what do you want to do?” and I’d say “let’s play around, let’s figure it out”, I’ve always had that leeway and as you say it’s done me well and the artists too, to have that leeway. If an artist wanted me to do something for them today, they’d have to come with that same approach.

Back when I was doing it, you had to have your own street credibility, but now you’ll find people are so buffered behind bodyguards. I could run into Tupac at a club or a bar in 1993, but you would never run into the likes of Drake or Justin Bieber in a club in 2016, no way, it’s too buffered now. And I think it’s a downside to the creative process, because when you become that isolated creativity suffers. Popular culture and social media has turned everything into a thing.

Chi has managed a wonderfully successful career as a photojournalist over the last 30 years. Starting out shooting the Hip Hop movement which he helped to define, he has gone on to establish himself as the photographer from that era and has used FotoWare’s FotoStation to license his vast library of unique images. His experiences of the business behind being a photographer and his perspective on the ongoing changes to the industry provide a fascinating peak behind-the-scenes for anyone.

If you like what you’ve read why not support the blog by subscribing to make sure you never miss a post – to read Part I of our interview with Chi click here!

To find out more about Chi:

https://www.instagram.com/chimodu/

https://www.instagram.com/mrleicam/

Uncategorized: http://uncategorized.com/

Images: Chi Modu

Source: https://www.fotoware.com/blog/the-business-behind-a-passion-chi-modu-interview-part-ii